Conventional wisdom has it that parks are visited far more intensely during economic downturns than during economic expansions. Here is a recent story summarizing:

Despite the recession, or perhaps because of it, 286 million visitors flocked to national parks last year, an increase of 10 million people.

…

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar speculated Tuesday that the increases may have come because families on tight budgets view parks as bargains, parks offered free visitation on three weekends, and parks attracted extra attention because of President Barack Obama’s visit to the Grand Canyon and Ken Burns’ documentary on the history of parks

…

He added that parks “provide vacation bargains for families living on a tight budget. They offer priceless opportunities to inspire adults and children alike with our wonderful natural, cultural and historic heritage.”

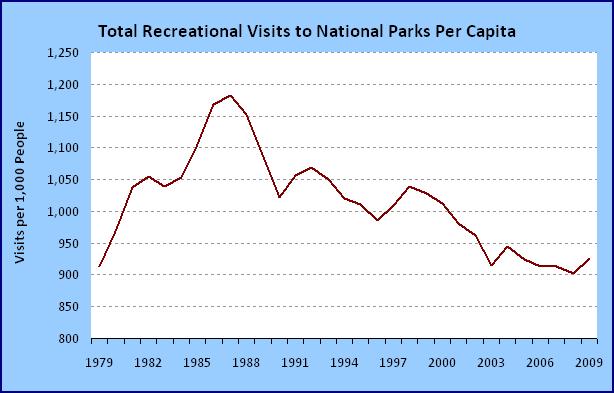

This should be coupled with the continued stories that “our parks are threatened” due to funding pressures and overuse. So I decided to look for myself for the real data. Below I show not just the gross number of visits to parks (which peaked in 1987 at 287 million) but rather I wanted to look at how park visits compare to the overall size of the U.S. population. What I found surprised me. Not only did gross park visitation peak in 1987, but park visit intensity is nearly 22% lower today than it was in 1987. In fact, in 15 of the previous 22 years park visitation as a share of the total U.S. population has fallen and visitation rates are at the same level as they were in 1979-1980 (I am working on getting visitation data back to 1904).

Upon further consideration, one aspect of this chart is not surprising – that we do not seem to see strong upticks in National Park visitations during recessions (I would suspect this is NOT the case for local state parks). Why? Because the “cost” of attending a National Park has virtually nothing to do with the admissions price for the park. For example, for me to fly my entire family of 4 from Rochester to Yellowstone National Park and to stay in a fleabag motel place for a week and get a cheap rental car would cost me (for a June 2011 trip booked now) $738 per person (or a total of $2,952) and that is staying 70 miles away from Yellowstone, doesn’t include the incremental costs of meals and other incidentals. Even if park fees increased by a factor of 5, that would not impact whether we made the trip or not. If the park entrance fees are any particular obstacle to most people, it means that folks would never be able to visit the parks under any circumstances. The notion that National Parks are a playground for the “everyman” is more than slightly exaggerated. Most people live thousands of miles from the most wondrous National Parks and even if you assumed folks could drive there for a far lower cost than I cite above, the time cost is extremely prohibitive, especially if you only get 2 or 3 weeks of vacation time per year.

The aspect that does surprise me is that relative visitation seems to be falling. In gross terms it is actually fairly flat since 1986 (with a sharp rise from 1979 to 1986 – maybe people tried to get all of their visits in before the supply-siders came in, sold off the lands to developers, and otherwise obliterated nature?). I don’t know how to reconcile this with the rhetoric and literature I get from the conservation organizations I am interested in, and with the rhetoric in the popular press about park popularity. I do know for sure that I am no more likely to visit the Grand Canyon today because the President went there last year. Maybe that works for some people, but not for me. I am certainly not taking a trip to the Taj Majal because of it either. What is more surprising is that these relative visitation numbers are falling even as the number and acreage of National Parks has increased – even as more park locations are being sited in and near major metropolitan areas. Maybe the visitation numbers to the Great parks (e.g. Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Smokies, Yellowstone, Acadia, Olympic, etc.) are robust and that visits to other urban parks have fallen. I’ll have to dig into the data when I get time.

Here is my last thought on the National Parks.

When at Teton Valley Ranch I made at least four day trips through Yellowstone, on the highway. You are correct in saying that one has to stay at least 75 miles away, unless you stay at the Yellowstone Lodge.

Maybe the Lodge has special rates for teachers.

One of TVR’s veteran counselors used to take along a metal wheel attached to a shaft, and had one of our campers set it on top of the ground. When Old Faithful was about to blow he’d yell to the kid, “Ok! Crank her up!” and the kid would start to turn the wheel like he was opening a great valve, and then Old Faithful would erupt.

As far as national park enthusiasm is concerned, I’d give more credit to Ben Bernanke and the celebrated outdoorsman Alan Greenspan than surfer Barack Obama. And other credit goes to James Baker and Edouard Scheverdnadze.

I think you have your supply-side dates wrong. Supply siders had their first effect in the early 80’s. Ronald Reagan inherited stagflation and turned it all around into prosperity. There is more to say on that story, but I was there, and vividly remember it all.

Our current economic woes are not the worst since Herbert Hoover, who was neither a free trader nor a supply sider, but rather the worst since Jimmy Carter.

In 1977 and 1978 William Miller did the same thing as Ben did, only with a couple fewer zeroes.

Wintercow, as you near your trip to northwest Wyoming, make sure to call for advice on flies to use when fishing, etc.

I’ve studied your graph, and I cannot think of any consistent theory to explain any of it. OK, the mountain goes to the foothills after the tax compromise, when the Reagan tax cuts were diluted, and since then there has been a relentless increase of regulation and taxes, but none of any of that makes sense regarding national park attendance.

My first thought is: how do they know? The same question applies to every number in Barron’s back pages, every number in Citi Bank’s weekly fed watcher statistics, all of the BLS numbers on productivity and employment, and the rest of the other derivative numbers you can find.

This is not to say that all numbers are worthless. The purchasing managers’ number is useful as an index, as are assorted inventory numbers, as are commodity prices. Prices are probably among the most reliable numbers. The rest you have to discount accordingly.