When you hear that the “US” spends approximately 18% of her GDP on health care, and that this figure has doubled in the past 30 years, and that the US experience is special insofar as expenditure increases here are larger than just about anywhere on earth, particularly when you learn that US health outcomes are not demonstrably better here than elsewhere, you would rightly be alarmed.

Why would you be alarmed? Because these data make it appear that we are wasting lots and lots of resources. A few observations here that many readers are already familiar with.

- Health outcomes in the US are regularly lambasted for being middle of the pack. But once you control for those factors that doctors themselves have little control over (such as the risk profile of the population and the fact that we deliver more at-risk babies than other countries) the US jumps to the head of the list for global health outcomes! But … not so fast. This does not change the underlying concern. After all, the US spends almost $4,000 more per capita than the rich country average. So even if you accept the adjustments above, we are not (apparently) getting that much better health outcomes, at least for those things that can easily be measured.

- As I’ve harped on dozens of times already: P x Q != Q. Expenditures do not equal costs. To say that the total expenditures on health care services in the US have increased is not the same as saying, “it costs more to deliver the same health services today as we did in the past.” I have seen extremely little work identifying what health care procedures are more costly today than in the past. That’s not even the right question. The right question is to ask, what does it cost to deal with a particular disease or problem today as compared to the past. If for example, in 1970 a heart condition requires surgery but today requires only medicine, how do we count this? If for example, in 1970 a heart condition was untreatable, but today can be treated but only with expensive drugs or surgery, how would we count it? If for example, a heart condition in 1970 was treatable similarly today but life expectancy after the surgery is higher today, how would we count that? Our pricing indices do what we call “hedonic adjustment” and quality adjustments for major goods like cars and homes, I am not familiar with efforts to do it with medicine.

- A related point to 2 is that looking at expenditures, even if we make the quality controls that I infer we should be doing above, still does not tell us anything about the health care problem. Why? Prices merely tell us how the gains from particular exchanges may be distributed. They say absolutely nothing, particularly in a regulated environment, about how many resources we are dedicating to health care today versus in the past. Raise your hand if you think that today we are dedicating truly twice as many of society’s resources to medicine as in 1980.

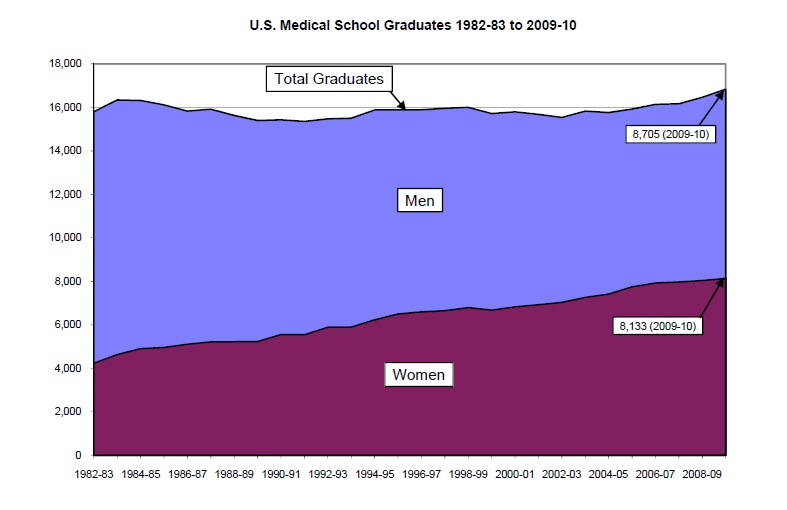

OK, so we graduate the same number of doctors today as we did 30 years ago despite the population being over 33% larger and despite the fact that real per capita income in the US is 67% larger today than at the same time. Of course there are millions of people dedicated to insurance, billing, sub-fields and the like – I am working on getting apples-to-apples data on this to present. In other words, to truly argue that health care costs are rising and out of control, you have to demonstrate that we are dedicating an increasing share of society’s resources to the provision and support of medical care, and that cannot be ascertained from the national income accounts. For example, if the government gave oranges away for free to people, and people stood in lines for hours to get those oranges, would you want to say that the orange sector was costless? It requires real resources to grow oranges and consumers spent real resources to ensure that they get them — in this case the price paid understates the true cost of the oranges. On the other hand, if the government guarantees a price of $43.21 per pound to orange growers but then also subsidizes the consumers of oranges to shield them from those prices, then the price received by producers dramatically overstates the real resources dedicated to the production of oranges. Many medical prices are determined contractually and via the government, and it is not at all clear that when you go to the doctor that the price you pay reflects anything close to the real costs of the visit. For example, I saw a doctor last week for 15 minutes and was billed $205 for the office visit. I did not use any technology, all I did was walk around the room and talk to the doctor for 15 minutes. Of course the guy coming in after me probably went for an MRI and spent 2 hours there, and he probably also only paid $205. Are we confident that in each case roughly $205 of resources were dedicated to medical care?

The fact of the matter is that if we really want to say something intelligent about our medical system we’d have to make a sincere effort to ask how many resources are being directed toward that sector to get particular outcomes, and we’d have to do that for all countries. Looking at how many green pieces of paper are allocated to the medical sector does not come close to what the real number ought to be.

Finally, in this week’s edition of “you can’t have it both ways” I cannot tell you how many blank faces I get when I use this same thinking as it pertains to environmental issues. I emphasize that looking at a price is an incredibly useful barometer of how many resources are dedicated to creating goods and services. Thus, if a Prius costs $30,000 and costs $1,000 per year to run for 5 years (ignore the time value of money) and if a Corolla costs $15,000 and costs $1,500 per year to run for 5 years, then the Corolla is undoubtedly “better” for the environment than the Prius. Why? Because the Corolla requires fewer valuable resources to build and run than does the Prius. Of course this is a simplification. The rub is this: my concerned environmentalists always ask the right question here — what if the price does not accurately capture the real resources that are embodied in the production and use of a good? For cars, absent taxes, it is likely that the prices are lower than the true costs since cars may cause pollution that is not paid for. Great. But this is exactly the point we are making as it pertains to health care. If there is ever a sector where the prices being paid do not match up closely to their real resource usage it is here – but ask your “E”nvironmentalist friends who also affiliate with the health care reform idea about whether health care price increases in the past decades are indicative of the problem in health care and they are sure to say yes. Ask them if goods prices capture the value of resources embedded in them and I am sure they will so no. Now, there IS a theory that can reconcile both of these positions, and it is an unobjectionable one – but my point is that “skeptics” on the economic way of thinking as it pertains to the environment first think about whether prices are right or not, while “consensus” thinkers on health care issues never imagine that prices could be anything but right. And it is that very idea that you cannot have both ways.

An additional even simpler thought on this …

Now that I’m older (early 40s) I spend a great deal more on fountain pens, good coffee, and shoes than I did when I was in my 20s. A LOT more. Does that mean there’s a problem? No, in this case it just means that I am now able to afford more of these better goods.