By now most readers are familiar with the factoid that 1 in 7 Americans is on food stamps. Here is the Wall Street Journal reporting/opining on Wednesday:

The Obama and Romney campaigns spent Tuesday sniping over whether the President deserves an “incomplete” grade, as Mr. Obama put it, for fixing the economy. The more revealing news was the Department of Agriculture report, released on the Friday before Labor Day weekend, that 46,670,373 Americans are now on food stamps.

That’s an all-time record, at an annual cost of $71.8 billion, $770 billion over a decade. Mull over that one for a minute. That’s nearly one of out every seven people—46 million citizens—who depend on taxpayers to buy one of life’s most basic responsibilities. It’s a good thing breathing air is free.

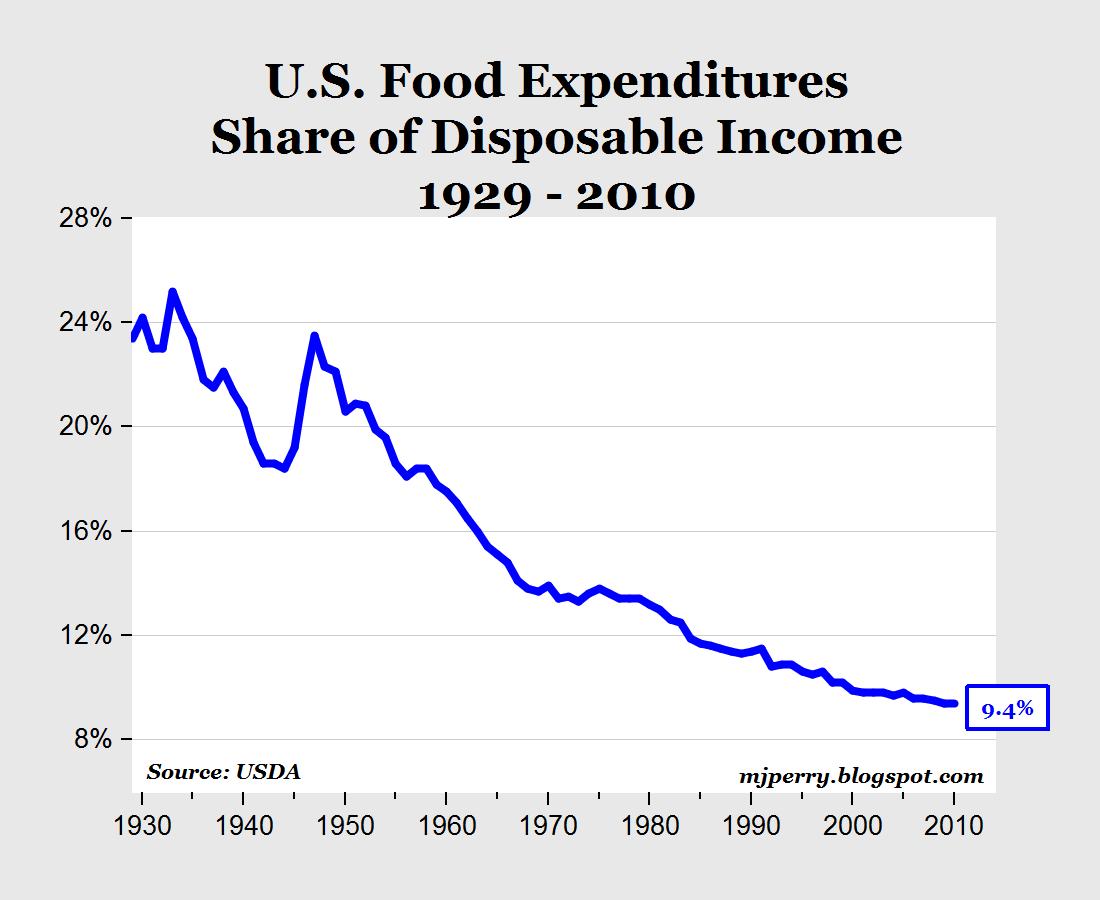

Regardless of what one things of the business cycle, reading that factoid surely should cause some hair to rise when we compare it with what has happened to the affordability of food over time. Here is Mark Perry’s chart:

So, as a share of disposable income, food prices in America are lower than they have ever been. This means that for all Americans having access to food is easier than ever before. And for those folks who wish to argue that compensation has “not kept up” (or whatever your favorite meme is) that only buttresses the point. The increasing affordability of food depends both on real food prices and on our disposable income. If disposable income has not increased, as many (misleadingly) claim, our ability to purchase food has still improved.

With regard to what is appropriate to help the poor with (or as it stands now, the lower middle-class) my instinct as an economist is to look at the margins for what people cannot afford and that which “we” deem important and then provide relief there (in lieu of a negative income tax). So it would seem to me that if we were serious about some of the major problems in America, we’d gut this program nearly entirely (after all, almost people can afford it) and focus resources on medical assistance and education instead. Or do folks mean to tell me that if you are a low income American, then there is no expectation at all that you use your income to take care of yourself? If people cannot be entrusted to spend their cash on feeding themselves, then what, pray tell, do you deem appropriate? And at what income level do we become magically capable of paying for our own food?

And many kids now get ‘free’ lunches and breakfasts at school: ( http://bit.ly/NfJJTt )

Two things:

1. The line below which one’s income must fall for “food stamp” eligibility is higher than the income level of an overwhelming majority of the global population. Poverty is relative.

2. The food give-away program is just a much a subsidy for the agricultural/food processing industry as it is for starving mendicants. The beef industry, for instance, would love it if the government gave away a free T-bone to everybody that’s behind on their tattoo payment.

Well-stated, Chuck.

I think Rizzo wants grade-school kids to starve, leaving them with nothing but green algae in their plastic bottles.

The easy answer is that we are subsidizing cable-tv, cellphones, and internet access. In other words, people use the margin saved on food for items that did not exist in 1930.

Realize also, that “food stamps” are no longer an alternative currency, but simply an electronic card. Therefore, the medium is more secure than it was 20 years ago. Thus, the items allowed (and restricted: imports, tobacco, alcohol) are, indeed, American agricultural products. While the direct beneficiaries are the nominally poor, the ultimate beneficiaries are the farmers. Yes, that includes ADM, but it also includes family farms. “Overall, ninety-one percent of farms in the United States are considered “small family farms” (with sales of less than $250,000 per year), and those farms produce twenty-seven percent of U.S. agricultural output.” (Wikipedia here.

Realize also that before 1930, 90% of Americans lived on farms. In my family before 1930, my grandfather worked in coal mines in West Virginia and SE Ohio. They had a cow; other neighbors had chickens, ducks, etc. That has long since ceased to be a common story. So, without our own cows and chickens in the backyard, we turn to farmers for more fresh produce.

I accept that doing away with food stamps would show a net savings. If nothing else, we would save on the machinery (bureaucracy) to produce and manage the program. Whether their absence would lead to an influx of Polish hams is not clear.

Also, I am not clear on the actual rules of the program, given NAFTA and the huge inventories of fresh produce from Mexico that I find in the grocery store.

The much-celebrated “small family farm”, a sacred institution whenever government spending is mentioned. But how is a small family farm closer to god than a small family plumbing business or a small family bookkeeping firm or even an individual head of the family employed as a janitor? The small family farm is no longer the bucolic scene described by Laura Ingalls Wilder, it is a business, operating on large acreages, with big investments in state-of-the-art capital equipment and technological innovations like GPS-guided tractors and genetically modified plants. This isn’t a bad thing, but neither is it right for the US government and its Department of Agriculture to subsidize, at the expense of other segments of the economy, an industry that is perfectly capable of operating on its own. There is no need for a “farm bill” or even a USDA.

Food stamps provide the path of least resistance for transfer spending. America’s poor aren’t really “starving” poor, but freeing up their food budgets for other spending is a politically viable 2nd-best proxy for pure dollar transfers. Combine voter hatred of dollar transfers and voter sympathy for a narrative of feeding the poor with the opportunity for Congress to shower agribusiness with public money: you’ve got a recipe for a big food stamps program.

Just to be fussy, measuring food prices as a share of per-capita disposable income won’t capture the income segment relevant to food stamps. Despite the real fall in relative food prices over time, it’d probably be more appropriate to look at the food share of the lowest quintile’s disposable income over time. Per-capita statistics don’t capture inequality stories.

Chuck’s right that poverty is relative, and demanding food subsidies in America seems silly since our poor aren’t starving like the actual poor out there. But I’d again emphasize that the food security fight is actually a proxy battle about income inequality.

Is this the U.S. average “Food expenditures share of disposable income”? Do you know if it is different for lower income people?

Extra credit for folks who answer Alex’s question. For those interested in a sneak preview, the answer is, “the picture looks the same” with the line shifted up a little (but surprisingly less than one may think). I’ll post it soon, but only after I set my freshmen to the task.

Looking for extra credit at every opportunity (isn’t extra credit, whether it be Fannie, Freddie, or the Fed the problem) I would presume Wintercow’s illuminating chart expresses food cost with average income.

But with food stamps, no one has ever had a quarrel with helping the people looking fondly at the big pieces in the garbage pail. Long before the New Deal, the hungry in our country have been cared for, and as Wintercow has presented often, in the land of the free, things are much better, decade by decade, century by century. That is the point the chart illustrates.

With all welfare, including food stamps, unemployment compensation, Medicaid, and whatever you want to include, the problem becomes acute when our country becomes poorer, or does not grow — I would say, does not grow as it should. Right now too many people are not working, and the natural response from most is to give the neediest help, not necessarily from government. But our present situation is not sustainable. (Yeah, fossil fuels are not sustainable after six or seven hundred years or more.)

While this may anger a thousand or more students at Rochester and elsewhere, the threshold for getting food stamps is way too high if there are forty million, more or less, getting them, especially if the recipients spend a pile on smart phones. The liberal approach to this problem is free phones with unlimited Internet access, and forced discounts at the Wegeman’s sushi bar (healthy!) using your food stamp card.

OK, I am callous.