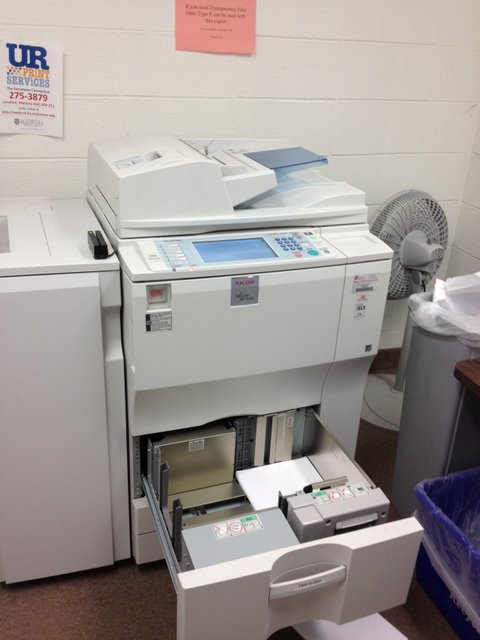

In this week’s episode of the Commons Chronicles, I bring to you … the office copy machine. I don’t make too heavy use of it, but I can assure you that when I do, I make lots of copies – mostly to print exams for my large classes. I typically need 600-1000 sheets of paper to print each exam. So, before I run copies, I fill the machine up as much as I can, and when done, I replace the paper, since that amount of copying runs the machine dry. But you can rest assured that if you did not first put paper in the copy machine and had to run any reasonably sized copy job, you’d run out.

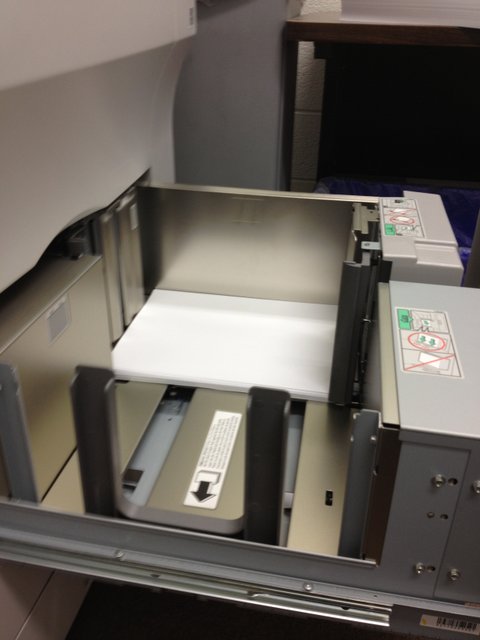

That was what our copier looked like before I ran off my Money and Banking exams the other day. Just five feet behind me is a giant stack of boxes containing printer paper. What is more fun than regularly knowing that “no one” fills the copy machine is something I am sure many of you have enjoyed. Walking into the same copy room to find the copier jammed and abandoned. I particularly like that. I’m no saint of course, but I don’t invade the copier commons.

In other news, in case any of you think that public health is about public health, check out this recent piece from the New England Journal of Anti-capitalism .. oh, I mean Medicine:

But from the glass-half-full point of view, the ban is not about attacking individual choice but rather about limiting corporate damage. If we see supersized drinks not in terms of the individual’s freedom to be foolish but instead as a kind of industrial pollution that is super-concentrated in impoverished neighborhoods,2 limits on drink size become a far different kind of regulatory measure. The target is not the individual: it is the beverage industry, corporate America. To be sure, the ban does not take on every industrial enterprise that is bent on profiting from inundating Americans with cheap, empty calories. But it does set what may be taken as a new precedent — though it’s also a move with deep historical roots.

…

By the second decade of the 20th century, public health efforts began to turn away from social reform and industrial regulation.

…

This century-old struggle is playing out again in the case of the giant-soda ban. The New York Times reports that even lawyers for the Bloomberg administration have strained to articulate a compelling public rationale for the policy. Do we interpret the ban as a narrow, quixotic measure that would present public health authorities as little more than scolding nannies? Or do we frame it in the grand tradition of public health activism, as a challenge to corporate and industrial practices that place profit above public health?

…

The aim of a ban on oversized sodas is to reduce the level of sugar and calorie assault that any single beverage dose represents. The assumption, of course, is that people won’t simply buy more and that intake will be reduced. But the target is corporate behavior.

A cap on beverage size would leave us with a soda cup half empty, but it opens an avenue to changing corporate practice. The New York City ban is limited to businesses that the city itself can regulate without causing undue hardship; addressing inconsistencies such as limiting the size of some drinks in establishments that receive inspection grades from the city health department while leaving others free to brim over would require similar regulatory action on the part of New York State. But if Bloomberg is bent on appealing Tingling’s ruling, it is time to start making a case with some muscle, which will require strong, active support from the medical and public health communities. If we can challenge the industries and businesses that profit by promoting bloated serving sizes, perhaps we can take on other corporate enterprises that similarly contaminate our social environment.

That last sentence is classic. I’d start by dismantling schools of public health. Because they are “non-profits” does not make them non-profits. Those enterprises indeed are contaminating (nice word, huh) our social environment. If we want to be utterly value-laden about it, then please give me a reason why pushing for the closure of those programs is any less of a serious proposal than imposing their will on evil “corporations.” What the heck does that even mean? Those schools are profiting handsomely by promoting bloated serving sizes of unhealthy nonsense. That must be stopped. And once we put an end to that, we can then take on other “corporate” enterprises like schools of education that similarly contaminate our social environment. By the way, the last time I was in McDonalds, they were trying to make a profit by selling me salad and yogurt. By the way, non-profits ARE ALSO corporate enterprises. Just sayin.

While reading the NEJM article, I found this passage to be interesting as well: “To be sure, paternalistic measures, practices that limit people’s choices for their own good, can be justified from an ethical perspective.” Really? It seems as if you can reject the objections of opponents to these types of “paternalistic” acts by merely assuming away the arguments opponents make.

In addition, I find the re-framing of these paternalistic proposals by saying it is not a restriction of personal freedom, but a restriction of corporate and industrial practices that place profit above public health to be particularly concerning. Given that just about every economic activity people engage in involves some corporation or businesses, what restrictions would there be in the types of actions public health “communities” can prohibit, or regulate?

However, reading the article, I am not sure how much the authors actually think that they are limiting corporate actions, and not the actions of individuals. After all, this statement from the article does not refer to the limitation of corporate actions, but the actions of individuals: “As with tobacco, it would take a tax on sugary beverages to effectively limit our individual ability to drink ourselves silly.”

If I can remember to do so, I will take a picture of an empty toilet paper holder, the ubiquitous symbol of the tragedy of the commons. I will try to find a high-class place here in North America. Next month, I’m going to Southern Europe, where toilet paper in public places is scarce, and that would be cheating.

Also, you have encouraged me to take pictures with my phone of sinks and floors in expensive restaurants, and in first-class lavatories of airplanes.