There is virtually no action to be taken by a business that could not be considered to run afoul of anti-trust legislation. Modern Anti-Trust is administered through two government agencies – the Justice Department’s Anti-Trust Division and the Federal Trade Commission. By the way the statue standing outside the FTC headquarters should give you an idea about what its real mission is. What is the difference between these agencies?

The Justice Department is supposed to deal with monopolies and business collusion. The FTC is supposed to focus on things called, “unfair trade practices” (read, if you are better at something than someone else, that is unfair). The Justice Department can only initiate anti-trust action by using the court system. The FTC on the other hand acts as judge, jury and executioner – in other words, when the FTC acts, it can do so outside of any formal court system and it has the autonomous power to shut down businesses and issue other directives and edicts.

The Justice Department is supposed to deal with monopolies and business collusion. The FTC is supposed to focus on things called, “unfair trade practices” (read, if you are better at something than someone else, that is unfair). The Justice Department can only initiate anti-trust action by using the court system. The FTC on the other hand acts as judge, jury and executioner – in other words, when the FTC acts, it can do so outside of any formal court system and it has the autonomous power to shut down businesses and issue other directives and edicts.

Firms can take their cases to the higher courts to appeal decisions from either the Justice Department route or the FTC route. Here is an example of how anti-trust action usually works.

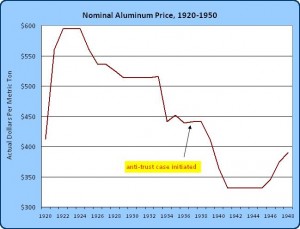

Alcoa (an aluminum company) was founded in 1888 and produced 10 pounds (that is not a typo) of Aluminum per day at $17,600 per metric ton. By the end of the Depression they were making 136,000 metric tons per year at a price of $441 per metric ton.

In 1937, the Department of Justice brought suit against Alcoa on 140 counts including charges of conspiracy, unfair treatment of competitors and excessive prices. The Justice Department got walloped in the TWO YEAR long trial (note that this was happening during the Depression – a really good way to encourage Alcoa and other producers to take risks and hire people!). But Justice appealed the decision … and in 1944 won their case – a full 7 years after the process was initiated. And here is why the court ruled against Alcoa (via RW Grant):

Alcoa insists that it never excluded competitors; but we can think of no more effective exclusion than progressively to embrace each new opportunity as it opened, and to face every newcomer with new capacity already geared into a great origanization, having the advantage of experience, trade connections and the elite of personnel.

As Grant put it, they were punished not for their wrongdoing, but because they were doing a superior job of providing the country with a vital commodity. You see, it is a crime to embrace new opportunities. You see, it is a crime to develop experience, expertise, a good reputation and good personnel.

Let’s look at what happened to aluminum prices during the time that the government was crucifying Alcoa.

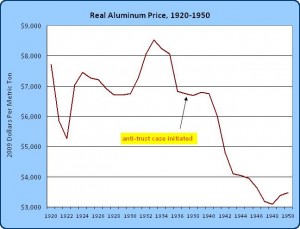

But those are nominal prices! In a world when prices tend to go up, we see aluminum prices falling in absolute terms. But at the start of the Depression there was a sharp deflation in the US – so perhaps the regulators were aware of this and were focused on the real prices of aluminum during this time?

Well, that spike in 1933 does correspond to the massive bank failures and contraction of the money supply by 1/3. But even thereafter, the price of aluminum fell sharply. In other words, there is absolutely no evidence that consumers were being harmed by high aluminum prices at this time. In fact, it is funny to think about two things:

- What happened to prices after the anti-trust ruling against Alcoa in 1944 (of course WW II ended, but we certainly don’t see a sharper drop)?

- Why would Alcoa get ripped for high prices during the Depression when President Roosevelt and his New Deal were primarily focused with keeping … prices … high during the New Deal? Remember, he instituted all manner of price controls and support programs to prevent prices from falling. So if Alcoa had allowed prices to fall by a lot they would have run afoul of the New Deal rules mandating high prices. But if Alcoa had allowed prices to rise because of its alleged monopoly position, they would have run afoul of anti-trust rules that they were ultimately convicted of anyway? How bizarre. And that is just the tip of the iceberg. We’ll explore other famous anti-trust cases in the future.

price fix by roosevelt

Thanks, Wintercow. It is always a good day when one learns something.

[…] and anti-trust is rarely about consumer protection. I was thinking about the old anti-trust suit brought against Microsoft over a decade ago. The […]