Humans are to electricity like fish are to water … or something close to it. Electricity has become so vital to our lives, yet so reliable, that we hardly think about it, perhaps even as we pay our monthly electricity bills. reflecting on our reliance upon electricity may lead one into a paradox, and it is one that I think is important for both climate discussions as well as our macroeconomic discussions. There are few things that I am looking at right now that would work as well, or at all, without electricity. And I am sure that if you made a similar observation 50 years ago, you would conclude that more stuff today is electricity dependent than back then.

So, is electricity more important today? It’s hard to say. On the one hand, when we are miserably poor and are doing everything by hand, the addition of a little electricity will go a long way. Perhaps we have clean and safe and reliable lighting instead of dangerous and dirty and expensive lighting. The gains we all get from being able to work, read, and play for a longer portion of the day are likely to be larger than the incremental gains from more electricity today. On the other hand, how much modern technology is possible without electricity? But if we examine some simple data, you might be a little perplexed.

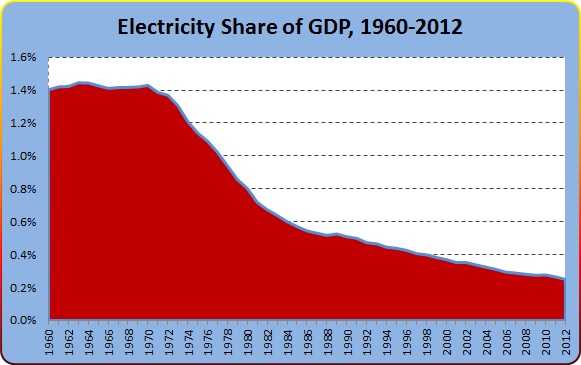

The chart above comes from a combination of EIA Annual Energy reports and BEA National Income and Product reports. It’s at best an approximation of how important electricity is to measured economic activity. I took the total amount of electricity consumed in the US and multiplied it by an estimate of the average price of electricity in the country (it includes taxes however). Then, I took this figure and divided it by GDP. What you see is that as a share of GDP, electricity expenditures are at an historical low – almost monotonically declining from 1.5% 50 years ago to less than .3% today.

There may be many reasons for this decrease. It could be the case that electricity generation is more efficient today than 50 years ago. It could be the case that electricity expenditures are decreasing because we use other things. It could be the case that we generate a LOT of value from other things which gives rise to GDP increases wholly outside the sphere of electricity’s influence. The (minor?) paradox is how can something as important as electricity be represented by such a small share of our economic activity? One possible answer is that since GDP only measures the direct expenditure on a good or service, the above chart is a bit misleading. Surely lots of the $16 trillion of GDP we currently produce depends a lot on electricity, and the expenditures on medicine, books, weapons, movies, and so on are all picking up some contribution of electricity to their production. HOWEVER, this actually captures the paradox. When I measured the price of electricity, I captured the total amount paid for it throughout the entire country. ,and so how much electricity expenditure is embedded in books, medicine, weapons, etc. is already depicted above.

The big message therefore has to be that our “GDP” isn’t really capturing everything we might want it to capture. I think it does a good job at measuring how much is spent on goods and services, but that’s it. I do not personally view it as a great measure of the VALUE generated by our entire economy. And this value can be larger or smaller than reported GDP. For example, if in making medicine, electricity and movies we make the environment unihabitable, then the measure of GDP overstates how much value we are creating since we don’t make great efforts to account for environmental depreciation. On the other hand, if our creativity makes our existing environment more liveable and if we face less risk today than we did in the past, then our measure of GDP understates how much value we are creating each year.

But the big thing GDP is missing is embodied by the chart above and by what I call the paradox. is how much “good” is created by our economy. When I spend 10 cents for a kilowatt-hour of electricity, our GDP measure is capturing this and this only. In some way it captures the cost of generating and selling that kilowatt-hour, but it does NOT in any way capture how much pleasure or value or “good” or “bad” that this kilowatt-hour produces. And think about what a single kilowatt hour of electricity does for you. In our home, it keeps the ENTIRE thing running for about 40 minutes. Our fridges and freezers are on. Our laptops and phones get charged. Our cable boxes and televisions operate. Our dryer and dishwasher and heat blowers run. Our 500 pound garage door opens. Our snowblower can more easily be started. Our lights are all on. Our oven works. Our basement water pumps work. And so many more things. Is having all of that staying on for 40 minutes really only “worth” 10 cents to our family.

Not in a million years. A better way to figure out how valuable this stuff is to us is to ask, “How much would I have to be paid in order to willingly sacrifice powering all of these things for 40 minutes?” You might do better by asking us for a range of time periods. How about 5 hours? What about 5 days? My bet is that number is a wee-bit more than 10 cents per kilowatt-hour. Indeed, there are a huge number of vital parts of our economy that are like this. Antibiotics cost almost nothing. And our GDP counts them as being virtually unimportant. So, how much would I have to pay you to have you live without the possibility of antibiotics? Or consider something even more radical. What about getting surgery. Have any of you ever had surgery? Did you have it with anesthesia? Well, that contribution to GDP is again almost zero. Let’s go into a hospital now and ask all of our surgical candidates, right as they are lying on the operating table, how much they would have to be paid in order to undergo their procedures with a few shots of brandy instead.

Which brings me back to electricity. We’re getting hammered by a really cold blizzard right now. And easily the biggest fear our family has right now is the power going out – and going out for several days as it famously has during some past winter storms up here in Rochester. Our heat does not work without electricity despite it being gas fired. Our oven does not work. I would have had to shovel 15 inches of snow for a 80 foot driveway because I can’t get my darn snowblower to start without plugging it in, and so on.

Now, given how important electricity is to all of us, I am pretty surprised at how often our power does go out. Indeed, the economic research I was able to scour up seems to confirm something I was already worried about:

. The research analyzes up to 10 years of electricity reliability information collected from 155 U.S. electric utilities, which together account for roughly 50% of total U.S. electricity sales. We find that reported annual average duration and annual average frequency of power interruptions have been increasing over time at a rate of approximately 2%

We’d hope that something as important as electricity would become more reliable over time. Cars have. Laptops have. Surgeries have. But not electricity. If “we” are going to continue to push hard toward “green energy” development, I don’t expect power reliability to improve. It’s very well understood that wind and solar are far more intermittent than our traditional ways of generating power, and cannot be scaled up and down according to variable power demands by customers. If we switched entirely to green energy absent battery technology it is no question that service interruptions would be worse than today. Why? First, the generators themselves are less reliable than the coal and gas and nuclear generators of today. Plus, the source of much of our my outages today are from transfer station problems, downed wires, and so on. The installation of much new green energy requires the installation of even more wires and transfer stations than our current system has. So it’s not likely to make downed wires, for example, LESS likely. How have economists and policy-makers included this in their cost-benefit analysis when they are talking about using green energy to solve global warming or other environmental problems thought to be caused by the traditional methods of generating electricity? I have not seen much evidence that ANY of it has been included outside of a footnote.

But reflecting on how important electricity really is for us, one can easily imagine that the costs of an unreliable or less reliable electric grid would be larger than any potential benefit we might get from greener energy, assuming unrealistically for the time being that those energies are themselves green, which in fact they are not, or at least not the shade of green many of us think. So, I’ve spend a little time perusing the economics literature for what we know about the economic impacts of power outages and electricity disruptions. I was surprised at how little research, particularly for developed countries, is out there. But here is a little sampling. It should be able to help you think about how much benefit green energy would have to provide in order to overcome not only its naturally higher economic costs already, but also the costs of less reliable power.

- This paper finds that the economic costs of power disruptions in Austria amount to about 17 Euros per kilowatt-hour disrupted, and this is for a disruption on a summer morning. That’s about $23 per kilowatt hour of value lost. I would venture to say that this number would be far larger in the winter, and larger in a richer country like the US. Let’s put this into a little perspective. Last year the US consumed about 4 trillion kilowatt-hours of electricity in total. This is about 11 billion kw-hr day. Suppose there was a 10% chance that we’d lose an average of one-day of power per year in the future, what would the expected cost be if we used the Austrian results? Well, at $23 per kw-hr lost, the full day would cost us a staggering $253 billion, so with 10% chance of power outage the annual expected value of the losses exceed $25 billion per year. And this is in the U.S. alone. Would transitioning the entire US energy grid to green power (which is impossible, certainly within 50 years of time) save this amount of global warming damage, wholly aside from the cost (higher) of those new energy sources?

- We know that nuclear power makes up just 20% of the electricity sector in the U.S. It is also a heavily regulated sector that went through some deregulation in the last quarter century. In this paper we learn that deregulating the nuclear sector by allowing the sale of reactors to private operators improved operating efficiency by reducing the time of power outages such that the annual economic benefits of the deregulation were $2.5 billion per year.

- This paper about losing gas fired electricity generation capacity in Ireland for 90 days would result in roughly a FIFTY PERCENT decrease in GDP over that time period, based on estimations.

- This paper estimates that a one-hour interruption of power costs about $4.00 per kilowatt-hour per unserved customer.

- This paper examines electricity disruptions due to seismic activity and estimates that a major earthquake could reduce GDP by 7% (in the affected area) due to electricity disruptions alone.

If you spend time in the trade and development literature I am sure you would find a lot more evidence for how important electricity is, but I think these papers give a flavor. Again ask yourselves, how much would you have to be paid to willingly give up power? Or better yet, how much would you have to be paid to be forced to give up power for some period, with certainty, but we don’t tell you when that period will actually be? I suspect that figure is quite large, and our measures of economic well-being miss this, as do most estimates of the costs and benefits of electricity generation.

Another finished chapter for Wintercow’s first best selling book, selling on Barnes & Noble for $4.50 in the Nook version. I bought Tom Clancy’s last novel today for two dollars more, but then he sold more books than all the living economics perfessers combined.

Regarding electricity, please let me add two personal comments to add to WC’s already rich and provocative essay:

1) Starting January 1, 60-watt incandescent light bulbs are not to be sold. We have to buy 40-watt bulbs, or spend more than triple to get “green” light bulbs filled with mercury, made by the Chinese, the same craftsmen who make the lights for your Christmas tree. (I am not, by the way, a Jingoistic Fair Trader.)

If I were running for Congress, I would promise to bring back the 100-watt and the 75-watt $1 light bulb. I would appeal to readers, and parents who want their children to read. My campaign manager would probably advise me not to say, “i do not care what those stupid Europeans say, let me buy a Hungarian 100-watt bulb.”

2) Few people have their minds concentrated on the availability of electricity as dairy farmers. (OK– if you own a carbon arc furnace melting iron, you have a big problem if it freezes up too.)

The barn cleaner, the refrigeration of the bulk tank, the pump running the vacuum for the milking machines, all fail, unless you are equipped as an Amish farmer we knew, who plowed his eighty acres with mules.

Not many of the Fellows at the Brookings Institution would be as well-prepared to take care of their herd, were they to suffer an interruption of power.

My first thought goes to something from my intro to economics book, why is water cheap and why are diamonds expensive.

Which delivered me to my second thought, the single biggest use of electricity is to pump water.

Interesting. This is like the argument over the relative importance of financial markets. We try to calm Marxian-inspired thinking by reminding people that financial markets only produce about 4% of GDP — but because of the network effects, we would likely be willing to accept much much more of national product in order to give it up.

So the trouble with these arguments is that *any* intermediary good, which is a lot of them, produces such network effects.

It would seem that we only get this economic argument about the “actual value” of these intermediary goods when we’re faced with either the reality, or as you’ve done above, the hypothetical of their collapse and disappearance in crisis.

It would seem that the “actually much higher value” you’re illustrating here isn’t normally incorporated into the cost of these goods because we’re not often reasonably threatened with their complete disappearance. The probability of crises of electricity and financial market meltdown is small, so the much-higher “crisis WTA value” you’ve highlighted gets discounted as such by agents with reasonably rational expectations.